Montreal, December 5, 2021

As one of Canada’s oldest craft organizations, La Guilde was at the forefront of the Crafts Movement and played a significant role in the shaping and development of the country's art ecosystem. Established in Montreal in 1906, the non-profit organization rapidly grew its activities across the entire country as well as outside its border. Many other Canadian crafts organizations, some of which are today well established, can trace their roots to La Guilde, known as The Canadian Handicrafts Guild from 1906 to 1966 and the Canadian Guild of Crafts from 1967 to 2017. In this article of Did You Know…, as promised in A Love Letter to our Founders: The Beginning, we explore how La Guilde and its partners expanded and adapted their activities to the needs and interests of the different communities in which it was operating.

6000 km: A Journey From Coast to Coast

“Possibly [La Guilde] is destined to be the means of carrying a fine and understanding sympathy from one Province to another. It may help to unite people who would not otherwise have a common meeting ground. [...] Here we deal with peoples of many tongues, many religions, differing standards, conditions that change constantly, and over an area that covers thousands of miles” (Peck 1929, 11).

In 1904, before the official incorporation, the women of La Guilde were “[...] convinced that the Craft Movement had to expand into all of Canada and that agencies could be developed to sell Canadian Crafts, not only in this country, but also in the United States, Britain and Bermuda” (Watt 1992, 32-33). The foundation of the Movement with the two exhibitions we’ve mentioned in A Love Letter to our Founders: The Beginning, truly shows the potential of the organization beyond its locality. There were no limits to their vision!

During the summer of 1908, the very first branch opened in the small town of Métis–today known as Métis-sur-Mer–in the Bas-Saint-Laurent region of Quebec. Managed by members of The Canadian Handicrafts Guild (later referred to as the CHG), the shop was an apparent success as it generated sales, gained the interest of the public, and stimulated craftsmen and women of that area (Annual Report 1908). This venture was the forerunner of many other branches, shops, and agencies spreading across and outside the Dominion (Canada). The main objective was always to promote Canadian crafts and increase benefits for workers. In 1910, the Extension Committee was formed and, after Miss Phillips' trip out West, a branch was opened in Edmonton, consisting of 50 members. By 1911, “[...] as a result of [La Guilde]’s efforts, some $30,000 [an estimated value of $874,000 today] [had] been paid to workers from Prince Edward Island to British Columbia. This sum represents money that would not have found its way into the hands of the Craftsmen throughout the country had it not been for [La Guilde]” (Pamphlet 1911, CHG). That same year, The Canadian Handicrafts Guild opened summer agencies in Chester (NS), Yarmouth (NS), North Hatley (QC), Cobourg (ON), Gananoque (ON), Vancouver (BC), and Victoria (BC), as well as permanent agencies in Hamilton (ON) and Summerside (PEI). These agencies were established by the CHG’s representatives, who travelled by train across the country to spread awareness and “[...] to encourage handicraft workers to use their imagination and creative ability to produce new and pleasing designs [...]” (Letter Mrs. Holt Murison 1928). The agencies served not only as selling points for Canadian crafts–thus developing the market and putting as much money as possible in the hands of the workers–but also as a place where workers could go for advice and develop their skills–thus raising design standards and product quality.

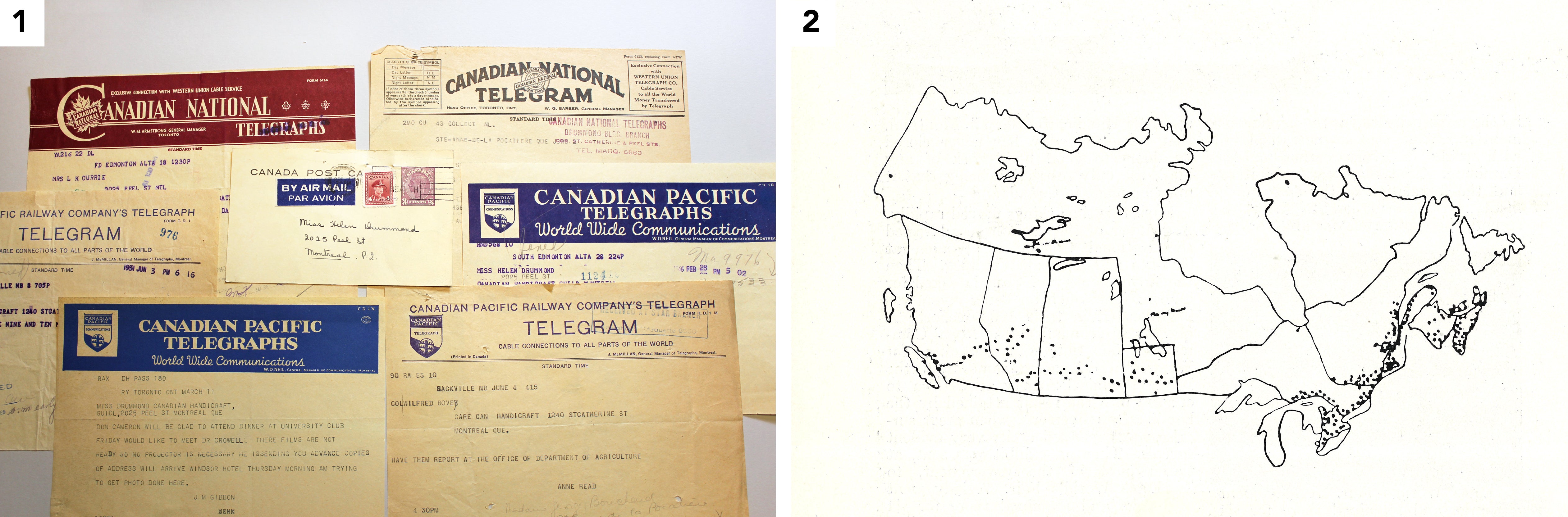

The increasing number of new agencies, branches, and shops in and out of Canada shows the success and receptiveness the Craft Movement had. By 1919, many summer agencies became permanent and many more opened in the United States: New York (NY), Chicago (MI), Philadelphia (PA), New Mexico, Detroit (MI), Boston (MA), Woodstock (NY), Huntingdon Valley (PA), Seattle (WA), Whitefield (NH), Waltham (MA), St. Augustine (FL), and in Camden (SC) and Bar Harbor (ME) during the summer months, to name a few (Annual Report 1919). However, the United States adopted the Fordney McCumber Tariff in 1922, which resulted in a significant drop in sales from those agencies since the tariff increased the price of imported goods. One by one, agencies across the border were closed and the CHG decided to focus on opportunities within Canada. Despite the success of the numerous Canadian agencies, communication challenges were quite apparent, especially considering the technologies available at the time. Amongst the many letters found–some of which longhand while others typed–delays between correspondences were substantive, testifying the difficulty of coordinating activities between the headquarters–located in Montreal–and the local agencies. As shown in figure 1, we also found in our archives several telegraphs, which allowed them to send short messages relatively quickly. Furthermore, the handmade goods collected in each agency were not always up to the high-quality standards encouraged by the CHG. At the same time, lack of funds prevented some agencies from directly purchasing the handmade goods from local craftspeople, which in turn needed money to continue producing. As you may notice, the struggle around funding such an endeavour was already very apparent, an issue we still face today.

Provincial Branches & Affiliated Societies

“It is to be hoped that this Branch [BC] as well as the others will, through the appeal of such patriotic and serviceable work [...] secure full and adequate support in the cities where they are established. By such means [La Guilde] is endeavouring to carry out its professed purpose, and let it be emphasized that the Branches are formed, not to act as selling agencies for what we might send them, but chiefly for the purpose of encouraging and fostering the many crafts to be found among the people within their own sphere of influence” (Armstrong 1929).

The federal charter of The Canadian Handicrafts Guild, headquartered in Montreal, allowed to appoint or recognize a society or group of persons as a branch of La Guilde. Although several branches and agencies were set up across the Dominion as early as 1908, it isn’t until the end of the 1920s that we officially see Provincial Branches. Subject to the constitution and by-laws of the national organization, each branch worked within its locality to promote the interests and advance the objects of the CHG, but with special reference to the crafts practised in that province. Provincial Branches paid an annual fee of $2.00, plus an additional 10 cents per member, to the national organization. They had to send a report of the activities carried out throughout the year, which were included in The Canadian Handicrafts Guild’s Annual Report–which is now part of La Guilde’s Archives. The national organization helped with provincial craft exhibitions “in every possible way”, and loaned inventory to and from other branches (Annual Report 1928). For the Annual Exhibition, organized by The CHG and held in autumn at the Montreal Art Association–known today as the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts–, each branch would send their best crafts, which were evaluated by the Technical Committee, and eligible for the Annual Prize Competition.

In addition to the Provincial Branches, Local Branches could be formed “[...] in any city, town or centre in the province where there is a group of ten or more persons interested in the work of [La Guilde]” (CHG Alberta Branch 1928). Anyone interested in the organization could become a member for a one dollar per year fee. Local Branches’ activities were smaller and tailored to the needs and interests of their members. For example, in Alberta, members organized regular classes and group meetings held in their homes. Each group focused on a specific craft: leather, petit point, copper tooling, glove making, rug making, embroidery, etc. Demonstrations and lessons were given to members free of charge. In return, members were asked to give future classes. The Local Branches had a structure much closer to what we may expect of a traditional guild. It is interesting to see how a similar structure was still at the heart of the national organization but on a much larger scope. Once again, we can see how the women of the time found creative ways to adapt to their target audience.

In 1927, the Cape Breton Home Industries in Baddeck (NS) affiliated with The Canadian Handicrafts Guild to become the Nova Scotia Provincial Branch. In 1928, Provincial Branches were opened in Vancouver (BC), Edmonton (AB), and Winnipeg (MB), with Saskatchewan and Prince Edward Island following in 1929, and New Brunswick much later in 1952. Each branch had considerable autonomy and their activities were not limited to organizing exhibitions. For instance, a few years after the first exhibition held at the Macdonald Hotel in September 1928, the Edmonton Branch was “[...] selling $500 [$8,000 today] worth of crafts and had begun buying equipment for [La Guilde]. Noteworthy was a four-harness loom purchased that year [1934]” (Kerr 1962, 3). In 1931, the Calgary Arts and Crafts Club became the Calgary Branch of The CHG and, by officially taking over the provincial responsibilities, became the new headquarter of the Alberta Committee. For more than 19 years, the branch held exhibitions, lectures, and demonstrations at The Hudson’s Bay Company store, in “the Green Room on the sixth floor, adjacent to the Elizabeth Room” (Kerr 1962, 5). It also worked closely with affiliated societies and cooperating institutions, including the Banff School of Fine Arts to implement weaving and design classes.

The British Columbia Provincial Branch opened a craft shop in 1930, located on the mezzanine floor of the Hudson's Bay Company store in Vancouver, selling items sent from other branches and local items such as baskets, pottery, and carved wooden buttons. The Manitoba Branch–formed after the New Canadian Folk Song & Handicraft Festival which revived great interest in local handicrafts–also opened a crafts shop which was operated by volunteers; each member had half a day of “shop duty” to complete every year. The Provincial Branch of Manitoba was very active and quite successful. By 1964, it had built an important permanent collection and a library, available to its members. Many branches produced a bulletin [fig. 6] including news on upcoming exhibitions, events, and conferences as well as detailed information on specific crafts and techniques: vegetable dyeing recipes, types of stitches with images and instructions, embroidery methods, etc.

Reorganizing the Constitution

“The very name “Guilde” implies the active cooperation of every member from the Pacific to the Atlantic” (Armstrong 1930).

In 1936, the articles of the Constitution and by-laws of The Canadian Handicrafts Guild were reviewed “[...] to ensure a larger measure of cooperation and mutual support between all those interested in the work upon which [La Guilde] is engaged” (Annual Report 1936). This restructuring led to the distinction between the the Provincial Branches and the national Headquarters–which focused on arranging travelling exhibitions, assisting new and existing provincial branches, advising the federal government, and cooperating with the Canadian Association for Adult Education and other Canadian and foreign associations. The Canadian Handicrafts Guild located in Montreal became the Quebec Provincial Branch, taking on all assets and liabilities, including Our Handicrafts Shops, while still providing for the national Headquarters “[...] office assistance and space as may be necessary for the proper conduct of its affairs [...]” (Report 1936).

The Ontario Provincial Branch & Other stories

In 1938, the Handicrafts Association of Canada–incorporated in 1931 in Toronto–adopted the federal charter of The Canadian Handicrafts Guild as an official Provincial Branch and changed its name to The Canadian Handicrafts Guild Ontario. Along with its craft shop, which was located on the northeast corner of Eaton’s new store on College Street, the Ontario Branch “[...] bought a number of looms, rented a large space over a bank at the corner of Spadina and Bloor in Toronto and started a weaving school. This was carried on for several years, until technical and art schools established such courses” (Marriott 1972, 14). We can note how the different branches were an important part of crafts education before school saw the need to add it to their syllabus. This branch was highly involved in developing training programs in Ontario; it presented a report “[...] to Dr. Y.J. Althouse, at that time the Provincial Minister of Education, calling his attention to this matter and asking for consideration in establishing educational facilities where craftsmen could train in the various mediums” (Marriott 1972, 14).

Many successful lectures and exhibitions were organized, notably the Canadian National Exhibition [fig. 10], and the Royal Winter Fair in 1939 and 1940, on which we learned in our archives that: “The exhibition was well attended and the management was very pleased. However, we had to receive our exhibits and display them (which took days) and pack and ship them all in an entirely unheated building in November. We worked in fur coats, sweaters, overboots and leggings and when possible in warm mitts. A terrible task for our voluntary workers” (Marriott 1972, 15). The devotion of the people involved with La Guilde will never cease to impress and inspire us.

The Craft House–a small lodge located in Grange Park [fig. 7]–was entirely restored and redecorated to become an exhibition space, work centre, and meeting place for affiliates, such as The Spinners and Weavers of Ontario and The Canadian Guild of Potters. In a pamphlet, we can read: “Any member or body wishing to hold a small exhibition or to rent the Craft House for suitable purposes may do so; though small, it is very attractive” (Pamphlet 1945).

A Provincial Branch–counting 100 members–was established in Yellowknife (NWT) in 1946. This branch worked mostly with Inuit communities located near that area. In the branch’s annual report of 1957, the president states: “After 5 years working with them I have finally been able to develop a much higher standard of workmanship, revive old patterns etc. I usually keep a supply of hides, lining material, threads, beads, and fur for trimming on hand [for] those women who are too poor to buy the necessary material. One of our workers must have made well over 20 pairs of mukluks before Christmas, all richly embroidered and very colourful. And now that our work becomes known, I receive orders from all over Canada. One steady worker makes between $50 to $100 a month” (Annual Report 1957). Once again, a good example of the demand for Inuit goods in the South.

Through Changing Times: An Evolution

It is “a matter of no small pride to the Province of Quebec” that the “Handicraft Movement began in Montreal” (Peck 1928).

With time, some branches became less active, and members drifted away “[...] perhaps because of the many opportunities in clubs and other organizations [...]” (Kerr 1962, 3). Indeed, many crafts organizations emerged in the second half of the 20th century, and La Guilde worked with an increasing number of affiliated societies. In 1971, E.G. Whitehall, President at the time, stated that “[...] the increasing interest in crafts and craftsmen has made it imperative, I believe, that some way be found to find a common voice in order to fully accomplish what all the many and varied organizations are attempting to do” (Minutes 1973). In 1974, the Canadian Crafts Council–known today as the Canadian Crafts Federation–was founded, to replace the National Canadian Guild of Crafts. The goal of this new organization was to “[...] provide a single viable national organization which would receive the support of all persons interested in the advancement of the crafts and could expect to receive financial support from government bodies” (Minutes 1973). Contrary to what many may think, La Guilde was always an independent organization and wasn’t subsidized or supported by any level of government, a reality that still remains today. Provincial Branches, then, became autonomous craft organizations with their own charter from their respective territorial government. Many mergers happened afterwards: the Ontario Branch of The Canadian Guild of Crafts joined the Ontario Craft Foundation [established in 1966] to become the organization we know today as the Ontario Crafts Council. In 1997, the Manitoba Branch of the Canadian Guild of Crafts closed, leaving its permanent collection and library to the Manitoba Crafts Museum and Library. The Quebec Branch of the Canadian Guild of Crafts, in Montreal where it all started in 1906, remained active and became what we are today.

Keeping the momentum and coordinating activities throughout all its branches was not a simple task for La Guilde. Each branch had its specificities and, as much as they needed autonomy, they also needed support and direction from the national organization. Although our archives include an unbelievable number of documents, letters, and pamphlets pertaining to all of their activities, some gaps made it difficult to draw an accurate portrait of all the branches, affiliated societies, and other types of organizations that contributed to La Guilde’s mission. With time, La Guilde transformed itself and adapted its structure and activities to better achieve its aim of developing, promoting, and preserving the skills and talents of Canadian artists. We are grateful to the women of La Guilde, and everyone who devoted countless hours, support, passion and who were convinced that the development of crafts was essential to the nation’s cultural and economic development.

Audrée Brin

Sustainability Consultant

With the precious collaboration of Genevieve Duval

REFERENCES

- “Annual Report of The Canadian Handicrafts Guild”, Montréal, 1908; 1919; 1928; 1936; 1957. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Armstrong, Henry F.. “Annual Report of The Canadian Handicrafts Guild”, Montréal, 1929. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Armstrong, Henry F.. “Annual Report of The Canadian Handicrafts Guild”, Montréal, 1930. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- “Canadian Handicraft Guild - Alberta Branch”, 1928. C12 D1 003 1928. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Kerr, Edith. A History of the Provincial Branches of The Canadian Handicrafts Guild in Alberta, 1962. C12 D1 017 1962. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Marriott, Adelaide. History: The Canadian Guild of Crafts, Histoire de la Guilde Canadienne des Métiers d’art, 1972. C12 D1 046 1972. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Mrs. H. V. Duggan, Letter to Mrs. Holt Murison, The Canadian Handicrafts Guild, March 9th, 1928. C12 D1 023 1928. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- “National Canadian Guild of Crafts 1972 Meeting Minutes” held April 26, 1973 at 2025 Peel St, Montreal (QC). La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- “Minutes of Proceedings of Joint Meeting of Canadian Guild of Crafts and Canadian Craftsmen Association” held March 3, 1973 at the Skyline Hotel, Ottawa (ON). La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Pamphlet, The Canadian Handicrafts Guild: Aim of The Guild, 1911. C11 D1 059 1911. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Pamphlet, Work and Aims of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild (Ontario), 1945. C12 D1 055B 1942. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Peck, Alice J.. Handicrafts From Coast to Coast. Montreal: The Canadian Geographical Society, 1934. Réimprimé par The Canadian Handicrafts Guild.

- Peck, Alice. Sketch of the Activities of the Handicrafts and of the Dawn of the Handicraft Movement in the Dominion. Montréal: Canadian Handicrafts Guild, 1929.

- Watt, Virginia G.. “First National Crafts Organization in Canada.” In A Treasury of Canadian Craft, edited by Sam Carter, 33-38. Vancouver, BC: The Canadian Craft Museum, 1992.

IMAGES

(1) Photograph of Telegraphs, 1931-46. C12 D1 055B 1942, C12 D1 007A 1946, C12 D1 041B 1931, C12 D1 081 1943. CHG C12 D1 Branches Affiliates.(2) Handicrafts Viewed Geographically in Handicrafts From Coast to Coast.

(3) Photograph of Trademarks, 1905-1943. C12 D1 046A 1931, C12 D1 081 1943, History, Trademark, Briefs & Surveys.

(4) Photograph of Memorial Plaque, 1906-1956.

(5) Photograph of Letters from Branches, 1928-1966. C12 D1 003 1928, C12 D1 023 1928, C12 D1 046A 1931, C12 D1 059 1961, C12 D1 041 1964-66, C12 D1 036 1965, C12 D1 042 1965. CHG C12 D1 Branches Affiliates.

(6) Photograph of Handicrafts published quarterly by the Handicrafts and Home Industries Division Halifax, 1944-48. C12 D1 042A.

(7) Craft House Ontario in Work and Aims of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild (Ontario). C12 D1 055B 1942.

(8-9) Photograph of Documents from the Ontario Provincial Branch, 1937-43. C12 D1 046A 1931, C12 D1 055B 1942.

(10) Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto in Work and Aims of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild (Ontario). C12 D1 055B 1942.

© La Guilde, La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

rXLBARYFoTfG

dUtOvaEGYVHpl

SufKYRJswqihZ

Bravo aux bénévoles et membres qui ont soutenu la production et la diffusion d’arts et métiers, et ce partout au pays. Merci pour cet article fascinant.

Very Informative, we the Canadian craftspeople and artists of today, owe a great debt of gratitude to all the dedicated founders and volunteers of La Guilde.

Thank you,

Donald Robertson

Leave a comment