Montreal, August 29, 2021

La Guilde has been involved in many aspects of the art world and has played a major role in shaping a space for Crafts in Canada. Our ancestors pushed the limits and questioned the world around them. They had a need to discover new fields and provide opportunities for many to express themselves. For many years, La Guilde has been known as a place to discover and acquire Inuit art. La Guilde was, in 1949, the first organization to sell Inuit art in the South in an exhibition exclusively dedicated to contemporary Inuit art. Although La Guilde was at the forefront of promoting Inuit culture and establishing a market for their art, they couldn't have been the only ones interested in this fascinating artistic endeavour with the Inuit. Looking through our archives, we were able to better understand what events led to the first sale of Inuit art and to the success that followed.

*As we are referring to original documents from the archives, the terms “Eskimos” and “Indians”, used in the publications at the time, are kept for historically faithfulness (see Note on Terminologies below).

Going North: A Beautiful Endeavour

To better understand how La Guilde achieved its endeavour into the North, we must look at the first encounters with the Inuit. Since the eighteenth century, the kablunait—whalers, traders (notably the Hudson’s Bay Company), explorers, and missionaries—have passed through the territory on their voyages. As many other colonial interactions have done in history, the Inuit were influenced by their contact with the Westerners and slowly began producing objects to trade with with the newcomers, some of which were even labelled as “art objects” by a few kablunait, notably John Murdoch in 1881 (Swinton 1987, 119-120). Miniature figurines of men, women, and animals carved in ivory and bone, small toys, amulets, and clothing representing Inuit life started to surface. These creations, most of them of small scale, were functional (tools, utensils, weapons, etc.) rather than aesthetics. This relation of trade continued throughout the nineteenth century and part of the twentieth century.

Getting Involved: La Guilde’s First Contacts

In its effort to protect and develop existing skills all around the Dominion, La Guilde tried to establish relationships with the people of the North, but the lack of accessibility and financial resources hindered their ability to do so. One solution they found to this major challenge was through the trading infrastructure of the kablunait, who had access to the very isolated communities and could serve as the link on the behalf of La Guilde. Not unlike the work done with the First Nations communities, our founders wanted to expand their activities to include Inuit communities. As mentioned in our previous articles, they had a desire to develop, promote, and preserve all types of handicrafts. The ivory and bone carvings they had seen brought back from explorations demonstrated know-how that ought to be preserved. What we find completely unbelievable is that they recognized the potential and were determined to find a way to broaden the market and expand their reach to those communities. After all, their mission was to give opportunities to those in remote areas so they could live from their craft.

As early as 1902, annual exhibitions included Inuit artefacts (sadly, we haven’t been able to find any visual accounts of that part of the exhibition). Documents state that small ivory and bone carvings were part of the display, and we even found a mention of stone lamps made out of steatite (Home and Handicrafts, 1902). In 1911, La Guilde prepared a royal offering for the occasion of Queen Mary’s coronation [pictured in figures 1-3]. The letter accompanying the offering stated that the gift included “an interesting group of examples of a number of the crafts, old and new, both primitive and cultivated, which are practised by skilled workers from the Eskimo igloo to the studio of the artist” (Dedication, 1911). It was a patriotic illustration of what Canada had to offer.

Spreading the Word Out

In 1912, The Canadian Handicrafts Guild invited the Norwegian explorer Christian Leden to give a conference in Montreal. The ethnomusicologist and composer is known as the first person to record film in the Arctic region. “Mr. Leden has just returned from spending several months among the Eskimos where he had been sent by the King and Queen of Norway and the University of Christiania to explore and gather ethnological data among the aborigines of the Arctics” (Announcement 1912). The event, entitled The Eskimos, their Arts and Handicrafts, depicted his stay in the Arctic with stereoscopic views and phonographic records of Inuit chants and music. The interest of La Guilde for the Inuit went beyond their carvings, it aspired to share their culture and raise awareness of the Inuit way of life. It is important to note that not all the articles and documentation of the epoch referred to the works in question as “art”. However, most of the endeavours of La Guilde used that term, which we believe says a lot about the value and importance given by La Guilde to the work of the Inuit. The activities carried on with the Inuit were a natural extension of the organization’s mission and “raison d’être”. Educational activities were an important part of La Guilde, and this conference is a perfect example of how La Guilde was committed to incorporate expertises and experiences from indigenous, immigrants, and local artisans in their events (Peck 1929).

Although La Guilde had branches in almost every province, the effort to reach the northern communities seem to be mainly from the Montreal and Winnipeg branch. In the 1920s, a few articles were published mentioning La Guilde’s desire to get in touch with more artisan. They all highlight the difficulties of having access to these isolated communities and the scarcity of the materials in these regions. One article goes as far as to say that “Eskimo carvings of great beauty have come to the Guild, and it is felt that the art of these northern tribes ought not to be lost” (Journal 1916). With this mindset, La Guilde was driven to push their research and seek alternatives.

Getting access: The first few exhibitions

According to our archives, the first-ever exhibition, dedicated exclusively to Inuit artefacts, that piqued the interest of the public was held at the McCord Museum (then the McCord National Museum at McGill University) in 1930. The exhibition included articles such as tools, implements, and weapons collected by Hugh A. Peck, the son of one of our founders, Mrs. Alice J. Peck, and from Forbes D. Sutherland’s collection which belonged to the Strathcona Ethnological Museum. The items from Hugh A. Peck's collection were acquired during his excursion on the S.S. Adventure in 1909 (primarily in Kuujjuaq, formerly Fort Chimo, Nunavik). Not unlike his mother, “Peck kept a detailed journal of his adventure, writing passages on the fur trade, the dangers encountered, the manufacture and use of certain tools by the Inuit and on his impressions of the waterscape, landscape and people he met” (Arctic Adventurers, McCord Museum).

The Montreal Gazette listed in great detail all the objects in the exhibition from utilitarian objects, items of clothing to small animals and toys. “A large case contains numerous implements and playthings made of ivory, which the Eskimo gets from walrus tusks and adapts to his various uses. A collection of little ivory pellets and beads, tied together with gut, shows what is used in the North as monetary change; the Eskimo is particularly fond of beads which he obtains from traders and these are found as decorations on many of his implements” (The Gazette 1930, 5). The exhibition definitely set the ground and the mood for what was to come. Adjectives such as curious, fascinating, and absorbing were used by the press to define this first exhibition. This was a clear sign that Montreal was ready for more work by Inuit and that there was a space for such creations.

As the interest in Inuit works grew, La Guilde started presenting more items whenever possible. During the 1931 annual exhibition [fig. 5] at the Montreal Art Association, there was a strong media reaction to the pieces in the show, so much that the Inuit collection was isolated in another article of The Montreal Gazette. “The exhibition, which is the most successful the guild has ever held, both in quality and in the attendance, provides a comprehensive and illuminating survey of the handicrafts of the Dominion. A particularly interesting collection of work by the inhabitants of the most northern portion of the country, the Eskimos, has been assembled for the exhibition” (The Gazette 1931, 9). From “exotic” garments to “fascinating” groups of carved seals, every piece in the show was deemed incredible.

Through the following years, La Guilde was mentioned numerous times in relation to Inuit works included in its exhibition. In 1939, the very first exhibition dedicated only to Inuit and First Nations took place at 2025 Peel Street. The event was advertised in the newspaper [fig. 7]. It stated: “Aesthetically pleasing and historically interesting examples of the arts and crafts practised by Indians and Eskimos on this continent centuries before the arrival of the white men and revived largely by the Canadian Handicrafts Guild are included in the special exhibit [fig. 8] which the guild opens at its new premises, 2025 Peel Street, tomorrow” (The Gazette 1939, 5; Montreal Daily Star 1939). What we find fascinating going through all these accounts is how the mission of La Guilde bleeds through the pages. It is clear that the efforts in the North were no different than the efforts in remote areas along the Saint-Lawrence River to revive handicrafts of all kinds. For the first time, along with the ivory and bone carving, we see a more extensive list of items made of soapstone such as stone pot, polar bear, and walrus carvings.

As mentioned earlier, the objects collected from the Inuit were sparse and difficult to come by at the time. Many accounts mentioned that it was highly dependent on the quality of the trapping and hunting that year. It was found that many Inuit would carve to counteract their regular activities and potential losses. La Guilde was starting to be seen as a resource and one of the organizations wishing to develop an art market for the Inuit creations. At the beginning of the 1940s, the Northwest Territories Administration of the Department of Resources and Development (later known as the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development), reached out to La Guilde to find an outlet for Inuit handicrafts. However, 1941 was a good fur year and the Inuit “were, therefore, not interested in handicrafts” (Swinton 1987, 125).

While the effort with the government wasn’t achieving the desired goal, La Guilde wasn’t discouraged and tried to find other ways to reach out. One of which was to send letters to an already established network, that of the nurses, missionaries and doctors’ wives located in the North, about the desire to establish a stable market. As the notion of what is “good” is highly subjective, La Guilde included examples and suggestions of the type of works they were looking for. They wanted to preserve the know-how of Inuits and make sure that they stayed authentic to their culture. Here is an excerpt that is particularly telling: “In our civilizations we have lost much of the skill that our ancestors had in adapting to their needs the things they found at hand. In any work we do with the Eskimo, it would be well to remember this and that we should encourage them to use their own materials and methods rather than copy ours. We have the responsibility of not letting them forget their own arts” (Suggestions, 1941). The letter also included a leaflet with examples from Museum collections and definitions of each type of works (i.e. basketry, carvings, etc.) that La Guilde wished to compile with the help of “anyone on the ground anxious to take part in the effort” (Lighthall, Annual Report, 1941).

A moment that changed everything

James Houston changed everything. Not only did he have access and acceptance from the communities in the North, but he also had a vision that very much aligned with that of La Guilde. We will make a separate article dedicated exclusively to James Houston, called Saumik by the Inuit. After returning from Port Harrison (Inukjuak, Nunavik) in the fall of 1948, Houston was sent to La Guilde by neighbours in Grand-Mère (QC). As George Swinton stated in Sculpture of the Eskimo, “the stage was well set for the new phase of Eskimo art in general, and of soapstone carving in particular” (Swinton 1987, 125). Houston saw beauty in the pieces made out of stone the same way La Guilde did. Colin J.G Molson, chairman of the Shop Committee, thought it was “all too good to be true” when Houston asked if La Guilde would sponsor him for further travels. From that point, we found dozens of letters between Molson and the Hudson’s Bay Company to build a partnership, used here to piece together the events that unfold (Letters 1948-1949; Report 1948). Once the Hudson’s Bay Company understood that this endeavour wouldn’t affect their activities and that Houston and La Guilde were interested in different types of works, they gave full cooperation to the project. The Hudson’s Bay would provide food, boarding, and transport while La Guilde would open a bank account with them to pay for the pieces selected by Houston. Carvings would be exchanged for chits (the currency used by Inuit in their dealing with the fur trade). Having learned that the people of Inukjuak needed additional means of living from Houston’s last travel, La Guilde sent him back there, as well as in Puvirnituq and Akulivik (Cape Smith), to begin the project.

It is important to note that La Guilde had to go through the Hudson’s Bay Company as they were the “owner” of the trading route which allowed access to the Inuit communities. Going through the established system shows that this was meant to be a profitable exchange as the Inuit were given a currency they could use in their daily lives. Furthermore, once they fully understood “the idea that we were prepared to buy a considerable quantity of their handicrafts [...] the place became a veritable hive of activity” (Houston 1951, 38). Houston’s mandate also involved creating ports in different areas where handicrafts could be sold through the system already set by the Hudson’s Bay Company. Port officials would accept carvings on the behalf of La Guilde to keep the project going long after Houston left the area. A few things are worth mentioning:

La Guilde had the policy of purchasing everything made by children to encourage the pursuit of these types of activities with younger generations.

Houston labelled everything in his selection as art. He saw the potential and artistic value in each and every piece.

Inuit have a strong relationship and understanding of their physical and cultural environments which shows in every aspect of their works. This deep connection, gained through observation of their surroundings, can be admired from the subject matter to the details and the shape of an animal.

Skills acquired when building tools or kayaks could easily be transferred to the making of art pieces.

La Guilde did not teach the skills necessary to produce these pieces, but rather encouraged and pushed the Inuit to use their imagination. As such, the artistic field they were creating could be true to their aesthetic and way of life.

In the fall of 1949, Houston had returned from his trip with about one thousand articles [fig. 9-12]. An exhibition was arranged for the end of November and was scheduled to last a full week. Much to everyone's surprise, all thousand articles sold in just three days. We’re pretty sure we can call this a success! This marked the first exhibition exclusively dedicated to presenting and selling Inuit art. Although La Guilde was not the first to attempt such activities, it was the first to truly succeed. Through dedication and perseverance, it recognized the need for an art market and found ways to advertise such a venture positively. This shows that when you enter a project with respect and integrity, people will want to get involved and find ways to actualize it. We are aware that not everything our ancestors did is perfect, but we keep seeing moments of true dedication that make us proud to work for an organization that didn’t accept the system put in place by the colonial government.

Genevieve Duval

Programming and Communications Manager

Note on Terminologies

In the present context, we ask everyone to refrain from using the terms Eskimo, Indian, or native. According the the Indigenous Foundation of The University of British Columbia (Terminology, Indigenous Foundation):

INUIT means “people” in Inuktitut. The term refers to specific groups of people living in the northern part of Canada who are not considered “Indians” under Canadian law.

FIRST NATION refers to Indigenous peoples of Canada who are ethnically neither Métis nor Inuit.

MÉTIS refers to a collective of cultures and ethnic identities that resulted from unions between First Nations and European people in Canada.

INDIGENOUS refers to First Nation, Métis, and Inuit.

NATIVE refers to a person or thing that has originated from a particular place. The term does not denote a specific ethnicity (such as First Nation, Métis, or Inuit).

INDIAN refers to the legal identity of a First Nations person who is registered under the Indian Act. The term “Indian” should be used only within its legal context.

REFERENCES

- Announcement (Mr. Leden’s Lecture), 1912. C10 D1 005 1912. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- “Arctic Adventurers - Hugh A. Peck.” McCord Museum. Accessed August 21, 2021. http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/en/collection/artefacts/L19.30.

- Dedication (on first two pages of the book), 1911. C11 D1 056 1911. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- “Canadian Handicrafts Guild Encourages Home Industry.” Arts, Journal, Saturday, March 18 (1916).

- “Handicrafts Of native Tribes Are Revived.” Montreal Daily Star, Wednesday, November 15 (1939).

- “Handicraft Prize List Announced: Exkimo Garments.” The Gazette, Saturday, October 31 (1931: 9).

- “Home and Handicrafts Exhibition”, 1902. C10 D1 001 1902. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Houston, James A.. “Eskimo Sculptors." The Beaver, June (1951: 34-39).

- “Indian Handicraft Exhibited by Guild.” The Gazette, Wednesday, November 15 (1939: 5).

- Lighthall, Alice M. S.. “Indian and Eskimo Committee.” Annual Report of The Canadian Handicrafts Guild, Montréal, 1941. La Guilde’s archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Peck, Alice. Sketch of the Activities of the Handicrafts and of the Dawn of the Handicraft Movement in the Dominion. Montréal: Canadian Handicrafts Guild, 1929.

- “Report of the Indian and Eskimo Committee”, 1948. C10 D1 022B 1948. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- “Suggestions for Eskimos Handicrafts”, 1941. C10 D1 017 1941. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Swinton, George. Sculpture of the Eskimo. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd, 1987.

- « Suggestions for Eskimos Handicrafts », 1941. C10 D1 017 1941. Les archives de La Guilde, Montréal, Canada.

- Swinton, George. Sculpture of the Eskimo. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd, 1987.

- “Terminology.” Indigenous Foundation. Accessed August 22, 2021. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/terminology/.

Images

(1-3) Gift for Queen Mary’s Coronation, 1911, C11 D1 056 1911.

(4) Greenland Eskimo, 1928-1930, C10 D1 010 1930.

(5) Exhibition at Montreal Art Association, 1931, C10 D1 011 1931.

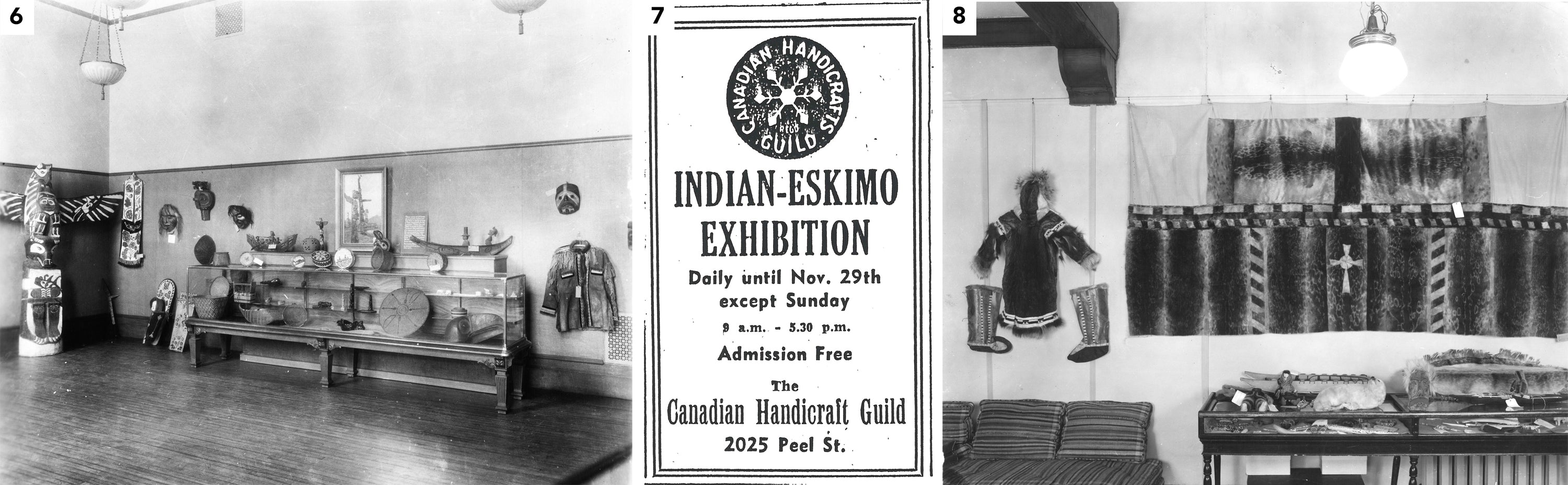

(6) Exhibition at Montreal Art Association: Indian Loan Section, 1933, C4 D1 033 1933.

(7) Newspaper Advertisement, 1939, C10 D1 015 1939.

(8) Indian-Eskimo Exhibition, 1939, C10 D1 015 1939.

(9-12) James Houston’s selection, 1949, C10 D1 026 1949.

© La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

Fascinant en effet; toujours hâte de lire la suite!

Fascinating background information. Thank you!

Leave a comment